The protracted standoff between Russia and Ukraine came to a head last week as Russia implemented supply cuts. But European gas hub prices hardly blinked. In the short term, the European gas market is well equipped to deal with targeted Russian supply cuts. Storage levels across Europe are high and a steady flow of LNG into Europe means hubs are well supplied. Europe also no longer depends so heavily on single transit pipelines, given the development of new transport infrastructure (e.g. Nordstream).

However the Ukrainian supply problems are reminding Europe of its dependence on Russian gas. European has shown a tougher stance against Russia this year (encouraged by the US). For example, Bulgaria recently pulled its support for Southstream. But while some members of the EU are pushing an aggressive stance, the response from large European importing nations has been more measured. Countries such as Germany and Italy are acutely aware of the key role that Russian gas supply plays in their energy supply mix, both in terms of meeting current requirements and for satisfying future incremental demand.

Broader or more prolonged Russian supply cuts would be a more serious issue, but one that is much less likely. Russia is well aware of its reliance on gas export income. And using supply as a political tool does not play well with the customers Russia is courting to the East. Russia is more focused on building long term export relationships than threatening existing customers. So the unpleasant reality is that as domestic European production declines, Russia is best placed to fill the gap. In this article we explore both the short term and long term dependence of Europe on Russian imports.

The short term impact

Anyone waiting for a big rally in gas hub prices as a result of Ukrainian supply cuts was disappointed last week. When the Russian supply cut finally came, it only acted to illustrate how oversupplied the European gas market currently is. Prices across the forward curve briefly spiked on Monday in a relief rally, before continuing their 2014 decline. Chart 1 shows the spike in the NBP Winter 2014/15 contract after the announcement, which was more than reversed on the following day.

The Russian supply cuts are primarily intended to resolve payment issues with Ukraine rather than as a broader threat to the rest of Europe. The cuts could not have been timed to have a more benign market impact, given a mild winter, plenty of warning, ample gas storage levels and alternatives for Ukraine to source gas across the summer.

For the Russia – Ukraine standoff to have a more meaningful impact on hub prices it would need to drag on towards winter. That is not out of the question given that gas supply negotiations are clearly linked to larger geo-political tensions. But Chart 1 shows little concern as to this outcome reflected in forward market pricing. Even in the case of a more prolonged dispute, Europe is much less dependent on Russian gas than in the previous periods of Ukrainian supply cuts (e.g. 2006 and 2009).

There are a number of supply flexibility options for filling a temporary import gap via Ukraine. Gas in storage provides an important backstop (typically flowing based on the opportunity cost of alternative supply sources). There is also room for increased Russian imports via other transit routes and some flexibility to ramp up Norwegian supply. But gas flows will be driven primarily by commercial & portfolio considerations. That is, gas will flow based on hub price signals.

The ultimate backstop in case of broader or more prolonged Russian supply cuts is increased LNG imports. Europe has large volumes of un(der)-utilised regas capacity. But importing LNG means paying up to compete with Asian and South American buyers. Spot LNG cargoes are currently relatively cheap for European buyers given a slump in Asian prices, but prices will likely increase again as Asian seasonal demand recovers into next winter. The last three winters have seen a 4-6 $/mmbtu price spread between European hub prices and netback Asian spot LNG prices. That is an unpleasant gap for European buyers to bridge over a more prolonged period.

The longer term problem

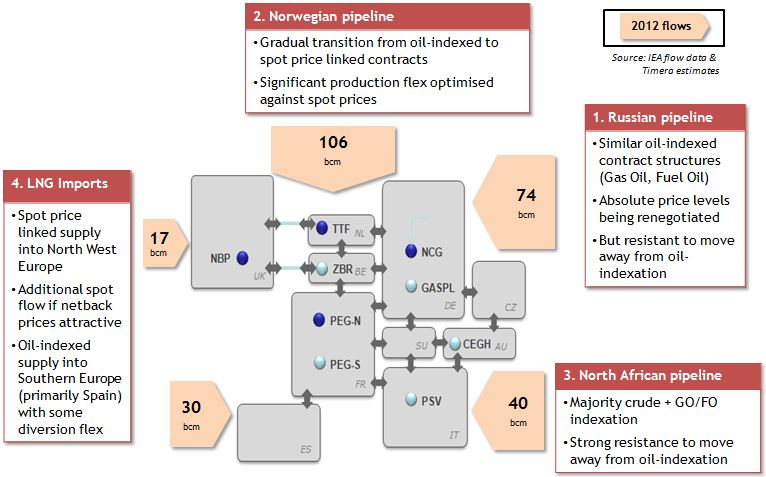

In the longer term, Europe faces a more difficult dilemma as to cost of gas versus security of supply. While there has been plenty of political rhetoric about striving for independence from Russian energy, Europe is facing the reality of declining domestic gas production. Chart 2 shows the key sources of gas supply into European hubs.

We have set out in more detail how these sources interact to drive hub prices. UK and Dutch supply is now in rapid decline, which could become more pronounced if seismic activity linked to gas production increases in the Netherlands. Norwegian supply has plateaued and is unlikely to offer significant incremental growth potential (as is North African supply). European shale gas production is also unlikely to make a substantial impact until well into next decade.

This leaves Russian pipeline gas and LNG imports as Europe’s two main alternatives for meeting incremental demand growth over the next decade. LNG imports offer supply diversification benefits, with regas terminals providing an important security of supply insurance role. But the cost issues with LNG imports are similar in the long term to those described above in the short term. Meeting incremental demand growth via LNG imports means Europe needs to compete with Asia for supply.

With LNG the only credible large scale alternative, Russia is well placed to meet incremental European demand. Estimates of uncontracted Russian production that could be sold into Europe range from 60-100 bcma. Russia has both the capacity and willingness to sell additional gas into Europe, as long as it does not undermine the oil-indexed pricing terms of existing supply contracts. So although it may be an increasingly uncomfortable relationship, Europe is set to remain dependent on Russian gas (and Russia on European payment) for the foreseeable future.