The UK’s 2001 implementation of the NETA wholesale power trading arrangements marked the ideological peak of a push towards liberalised wholesale power markets in Europe. Power market liberalisation followed across Europe with varying degrees of enthusiasm. But by the end of last decade, the UK had already signalled a return to a more interventionist policy stance with its vision for an Electricity Market Reform (EMR) package.

Growing concerns over security of supply and decarbonisation targets, have led the UK government to develop an EMR policy toolkit that allows it to target specific generation technologies. As EMR has evolved, it has become increasingly clear that the government intends to use this toolkit to drive the UK capacity mix. There is a growing risk that this path will end with the funeral of the wholesale power market, with a government directed ‘central buyer’ of capacity emerging from the ashes. This outcome may currently seem to have a low probability, but it warrants careful consideration over a strategic planning horizon.

UK market redesign signals the way forward for Europe

The UK is Europe’s ‘canary in the coal mine’ when it comes to dealing with the side-effects of government intervention to support renewable capacity. The UK power market needs to deliver new conventional capacity this decade to avoid a capacity crunch.

Most other European power markets can fall back on a current capacity oversupply situation, the result of a post-crisis slump in demand and support for renewable build. This reduces the urgency of having to tackle some of the difficult market design issues the UK faces. But these issues will eventually need to be dealt with across Europe.

Just as the UK led the push towards liberalisation in the 1990s, it looks to be leading the retreat back towards central planning this decade. It remains to be seen whether this retreat will be structured and orderly, or a more panicked response to the looming security of supply threat. Either way the path of UK energy policy is likely to be an important signal as to the future policy direction across European power markets.

The UK plan for a ‘third way’

There are broadly two models for electricity market design:

- A competitive wholesale market with transparent rules, strong independent regulation and a ‘sharp’ (cost reflective) market price signal to induce investment.

- A centrally administered solution where an independent body with a clear mandate uses a transparent approach to determine and deliver against capacity targets (e.g. via capacity auctions).

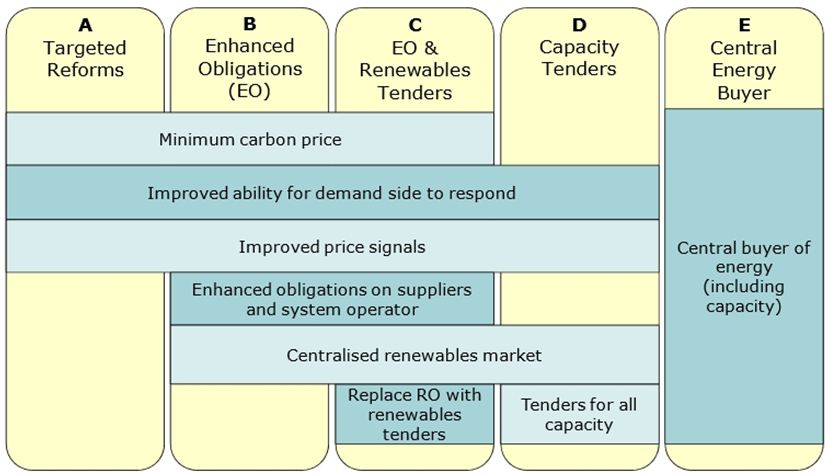

But the UK government has tried to steer towards a dangerous middle ground (as we set out previously). The origins of that middle ground came from Ofgem’s Project Discovery conducted over 2009-10, with a consultation process run around a set of potential policy intervention packages set out in the chart below.

Project Discovery was intended to offer the government a menu of potential market intervention mechanisms. But rather than choosing to:

- make targeted reforms to the existing wholesale market (box A) or

- opt for a radical shift to a ‘central buyer’ solution (box E)

DECC instead chose to layer everything on the menu into a poorly designed and unnecessarily complex mix of inconsistent market interventions. It was this process that has evolved into DECCs EMR policy package that is currently being implemented via the Energy Bill.

Progressing towards central planning

The EMR policy measures have not had a happy history to date. Piecemeal intervention to support low carbon generation technology has distorted wholesale market price signals and incentives. Driven by concerns around security of supply and renewable targets, the government has increasingly targeted policy measures to influence the build of specific generation technologies as summarised in Table 1:

Table 1: EMR policy intervention measures by generation technology type

The government’s vision for EMR is to create a new and improved wholesale market for a low carbon world. But EMR is undermining investment based on wholesale market price signals. Regulatory inconsistency and uncertainty is also substantially increasing the cost of investment capital. As policy intervention measures are layered on, investors are losing confidence in returns driven by an increasingly distorted wholesale market.

In reaction, investors have turned to lobbying the government to ‘underwrite’ investment returns via the EMR mechanisms being developed. The support package recently served up to deliver EDF’s Hinkley Point nuclear plant should be enough to make every British consumer’s stomach churn.

Policy design by lobbying and intervention is creating a circular feedback loop that is slowly but surely moving the UK power market towards a centrally planned solution. This is a path that poses large and unnecessary costs onto the UK public, particularly because of the higher cost of capital required to deliver new capacity. If a centrally planned solution is to be the end game then it would be much more efficient to move there with purpose and intent.

The risk of a central buyer end game?

The problem with EMR is that it has created a set of circumstances that are vulnerable to a political change of tack. If for example a serious capacity crunch materialises later in the decade, the government of the day could well make a concerted grab for control of the power market. Not by re-nationalisation of power companies & network assets but via a move to a central buyer approach.

Under this outcome the liberalised wholesale market would likely be assigned to the scrapheap and replaced by capacity auctions to meet government mandated targets. Ironically, the increased transparency of this outcome may result in a better deal for the UK consumer than the complex uncertainty of EMR.

It is also possible that there is a more gradual transition away from the current wholesale market design. The recent Labor Party energy policy statement proposed a move back to a gross pool market, accompanied by measures to break up the ‘Big Six’ incumbent utilities. But such a move assumes that the government of the day has the time to work with the private sector to implement such a transition. If the catalyst for change is an imminent threat to security of supply, a central buyer solution may give the government a greater degree of control more quickly.

A move to a ‘central buyer’ driven market would have serious implications for the business model and asset values of most energy companies & investors with a UK market presence. Investment would no longer be driven by wholesale market price signals but by some form of government driven signal (e.g. via long term capacity auctions or offtake contracts). While this could ultimately mean returns on new asset investments are more secure, the transition from wholesale market to central buyer is unlikely to be a smooth one for existing asset values.

In our view the probability adjusted impact of a central buyer outcome is high enough to consider as a serious business risk over a 5-10 year strategic planning horizon. The Labor Party’s recent policy announcement, while poorly conceived, is an indication of the mood for more radical change. The probability of a policy shift is only likely to increase as the capacity margin tightens and the EMR policy mechanisms come under pressure. It may be prudent to spend a few minutes considering the portfolio impact, mitigation steps and business model implications of a major shift in power market design.