Long term contracts play an important role in enabling the owners of flexible gas and power assets to monetise asset value and manage market risk. Common examples in power markets include tolling contracts, power purchase agreements and fuel supply agreements. Just as common in gas markets are capacity contracts on gas storage facilities, pipelines and regas terminals.

Long term contract (LTC) pricing is often a key driver of an asset investment case. The negotiation of contract pricing terms can be pivotal in getting past the Financial Investment Decision (FID) hurdle or raising debt financing for new assets. Long term contract pricing also typically plays an important role in determining bid price levels and financing terms for transactions involving existing assets.

While the importance of LTCs is clear, they present a key challenge. It is difficult to come by transparent benchmarks for LTC pricing. Pricing terms are usually closely guarded commercial secrets and the unique terms of specific contracts make it difficult to compare prices across contracts.

In this article we recognise these constraints, but focus on a structured way to understand & quantify drivers of LTC prices. This article follows on from two previous articles in a series we are publishing on LTCs:

- A revival in the contracting of flexible assets

- Long term contract pricing: counterparty motivations

5 key drivers of LTC pricing

The first thing that is important to recognise is that forward markets drive LTC value. This is the case even if the duration of the LTC extends well beyond the forward market horizon.

Growing liquidity in European gas and power markets means that the pricing of LTCs is underpinned by the prevailing forward price dynamics against which LTC value can be monetised. This is reinforced by the fact that LTC pricing is increasingly being influenced by trading focused intermediaries e.g. commodity traders, banks or other energy trading desks. These players may not have a specific portfolio requirement for LTC flexibility, but are prepared to price and monetise LTC value using underlying commodity markets.

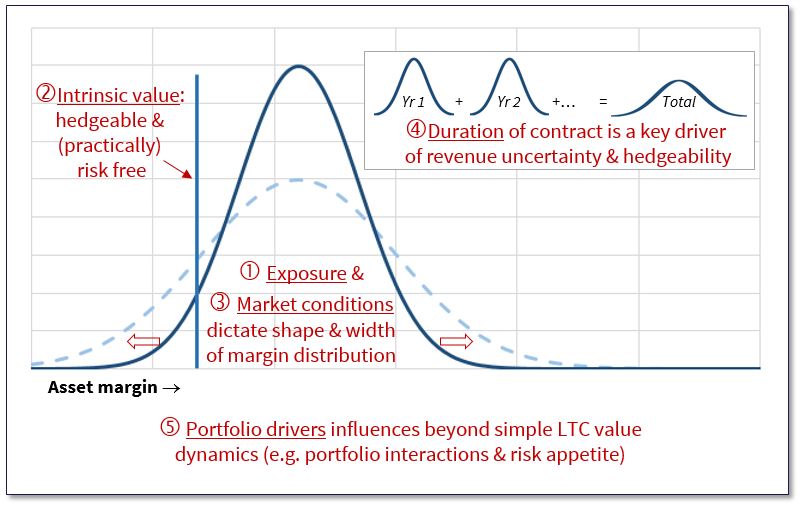

To put some structure around how LTC prices relate to underlying market dynamics it is useful to deconstruct price drivers into five key categories set out below.

- Exposure: The structure of LTC pricing terms in relation to underlying commodity prices (e.g. fixed price, price indexation, upside sharing or cap & floor terms).

- Intrinsic value: The degree to which LTC value can be hedged against current forward market prices (i.e. the ‘in the moneyness’ of the contract).

- Market conditions: The prevailing market pricing of flexibility contained in the LTC (e.g. driven by liquidity, price volatility, pricing/availability of alternative forms of flexibility).

- Duration: The term of the contract which influences available liquidity to manage LTC exposures as well as the level of uncertainty over future price evolution.

- Portfolio drivers: Other portfolio related value driven by factors such as ‘insurance premia’, risk limits, security of supply mandates or strategic considerations.

Chart 1, illustrates how these 5 key drivers relate to asset margin distributions.

The influence of these 5 drivers can vary significantly by contract, underlying asset and market. For example:

UK interconnector: the pricing of fixed price UK electricity interconnector contracts is strongly influenced by relatively high intrinsic value given the prevailing forward market premium of UK over Continental power prices (i.e. LTC pricing is driven by the fact that interconnectors are deep ‘in the money’).

German fast cycle storage: long term contracts on fast cycle gas storage capacity have very little intrinsic value but are strongly influenced by market conditions e.g. the level of prompt gas price volatility and the pricing of alternative sources of gas deliverability.

Southern European pipeline capacity: The value of LTCs on gas pipeline capacity into Italy or Spain can be strongly influenced by strategic portfolio considerations. Non incumbent players may pay a premium for external access to liquid European hubs, given cross border capacity availability constraints.

To illustrate how the five LTC pricing drivers interact, we return the UK CCGT tolling contract example we set out in our first article in this series.

A UK tolling contract case study

This case study has a current relevance given that a number of CCGT project developers are trying to structure tolling contracts to support the bidding of CCGT development projects into this year’s UK capacity auction.

Exposure:

The structure of LTC pricing terms determine contract exposures to underlying commodity prices. Tolling contracts are typically structured on a fixed price annual capacity fee basis (i.e. £/kW/yr). This acts to transfer market risk from the power station owner to the tolling counterparty. But tolling contracts can also contain indexation, upside sharing or availability risk sharing terms that mean that the owner retains a portion of market risk.

Intrinsic value:

CCGT intrinsic value is a rapidly evolving concept in the UK power market. CCGTs have increasingly come back into merit in 2016 as gas hub prices have declined. This supports the value of longer term tolling contracts, which have been difficult to source over the last 5 years as load factors have declined. However forward clean spark spreads remain relatively weak which has a strong influence on the way that tolling contracts are priced.

Market conditions:

Aside from spark spread levels there are several other market related factors that impact tolling contract prices. A significant portion of UK CCGT value is realised in the prompt horizon as power price granularity increases. Power price volatility on the other hand has been relatively low which reduces the value of CCGT flexibility. The depth of buyer interest has also been limited given negative sentiment on CCGT value and the fact that utilities (arguably the natural buyers of tolling contracts) are encumbered with write-downs on their own CCGT assets.

Duration:

The term of UK tolling contracts is a key factor driving pricing. A number of counterparties are prepared to price 3 to 5 year tolling contracts given an ability to hedge a significant portion of forward exposures (with UK power market liquidity reasonable out for 3 to 4 seasons). But a 7-10 year tolling contract to support financing of a new CCGT project may be priced at a substantial haircut to reflect a lack of forward liquidity over this horizon and considerable market uncertainty in the 2020s.

Portfolio drivers:

Portfolio drivers have not had a strong influence on UK CCGT tolling contract value. This could be different if UK utilities had a requirement for gas-fired flexibility to hedge their supply portfolios. But existing flexibility from vertical integration has neutralised this impact. Pricing is instead firmly focused on the expected value of tolling contracts that can be monetised against underlying power, gas and carbon markets.

So now we’ve considered 5 key drivers of LTC prices and a case study, how do we approach putting a number on LTC price levels?

5 key drivers of LTC price quantification

The most sensible way to approach LTC price quantification is to use a similar approach to the trading desk counterparties that typically set LTC price levels. The techniques used to value LTCs are becoming more standardised across trading desks from utilities, commodity traders or banks. These again lend themselves to deconstruction into 5 key drivers:

1. Intrinsic value: LTC value that can currently be hedged against forward curves typically defines an important lower bound for LTC price level. It is transparent and relatively easy to calculate.

2. Full merchant value: The most important benchmark determining LTC price levels is the expected merchant value that can be generated via the contract. On top of intrinsic value that can be locked in today, this consists of:

- value beyond the liquid forward curve horizon

- shape value as forward contracts become more granular closer to delivery, allowing additional flexibility value to be monetised

- value from using LTC flexibility to respond to shorter term price volatility (often termed extrinsic value)

Quantifying expected merchant value is typically done using complex models that capture the interaction between (1) commodity price uncertainty and (2) asset / contract flexibility and constraints. However, model complexity comes a with a health warning. Robust parameter estimation, sensible treatment of practical value monetisation issues and experienced judgment in interpreting model results are a prerequisite for effective modelling.

3. LTC haircut: A counterparty bidding for an LTC will not pay its expected merchant value. Instead the counterparty will discount expected value to reflect its costs of monetising LTC value. The most important costs are associated with risk capital (to back potential swings in LTC value) and market transactions costs (e.g. bid/offer spreads & credit costs). These costs can be quantified and compared with empirical benchmarks to estimate LTC haircuts.

4. Historical value: Estimating LTC value based on historical market conditions provides a clean and transparent measure to benchmark modelled expected merchant value.

5. Transaction implied value: There are often interesting LTC value benchmarks that can be implied from relevant asset transactions or other LTC prices. These can provide very useful information on market conditions (e.g. expectations on volatility or existence of any portfolio driven value).

Narrowing in on pricing bounds

Using these approaches to bound LTC price quantification provides a much greater insight than a simple scenario based approach. It also acts to build confidence around upper and lower pricing bounds and key pricing inflection points.

Ultimately the price of a specific LTC will come down to a unique set of circumstances. But having a structured framework for understanding and quantifying the drivers of LTC pricing can make life much easier.

Article written by David Stokes & Olly Spinks