Green hydrogen project investment cases depend on securing policy support. The most important requirement to qualify for ‘green hydrogen’ policy support is sourcing ‘green power’.

“Hydrogen investors are consistently underestimating the benefits of alternative power sourcing strategies”

The EU recently set out its guidelines for what constitutes ‘green power’. In today’s article we look at 3 different power sourcing models for green hydrogen projects and their implications for investment economics & risks.

What is ‘green power’?

The EU Delegated Act published in Feb 2023 provides a set of rules for sourcing ‘green power’. The 3 main conditions can be summarised as follows (note our summary simplifies what is a complex set of rules):

- Temporal – sourcing of green power must match electrolyser consumption at monthly granularity until 2030, with stricter hourly matching required after

- Geographical – green power must be sourced from the same market bidding zone (or an adjacent zone where sourcing helps alleviate network constraints)

- Additionality – a more complicated condition that is waived until 2028, but involves ensuring that the green power is sourced from incremental low carbon generation sources that don’t benefit from other policy support.

Importantly, power is also deemed to be ‘green’, regardless of the conditions above, if it is purchased from the wholesale market (in the same bidding zone) at a price either:

- Less than 20 €/MWh, or

- Less than 0.36 times the EUA price (currently 32 €/MWh with an EUA price of 88 €/t).

This market sourcing route is important, because it is set to significantly reduce the cost of feed power for electrolysers over time.

As growth in RES capacity pushes down wholesale market prices in periods of high wind & solar output, increasing volumes of wholesale market ‘green power’ will be available. Access to market sourcing of green power is therefore a key element of an electrolyser sourcing strategy.

How does an electrolyser project source green power?

Complying with the green power conditions above can broadly be done in one of three ways: (i) build your own renewable (RES) asset (ii) buy power from a 3rd party RES asset via a PPA or (iii) enter into a more structured PPA with a RES aggregator / trader to enable more dynamic sourcing of green power e.g. across a portfolio of RES assets/PPAs and the wholesale market.

Let’s consider these 3 models one by one.

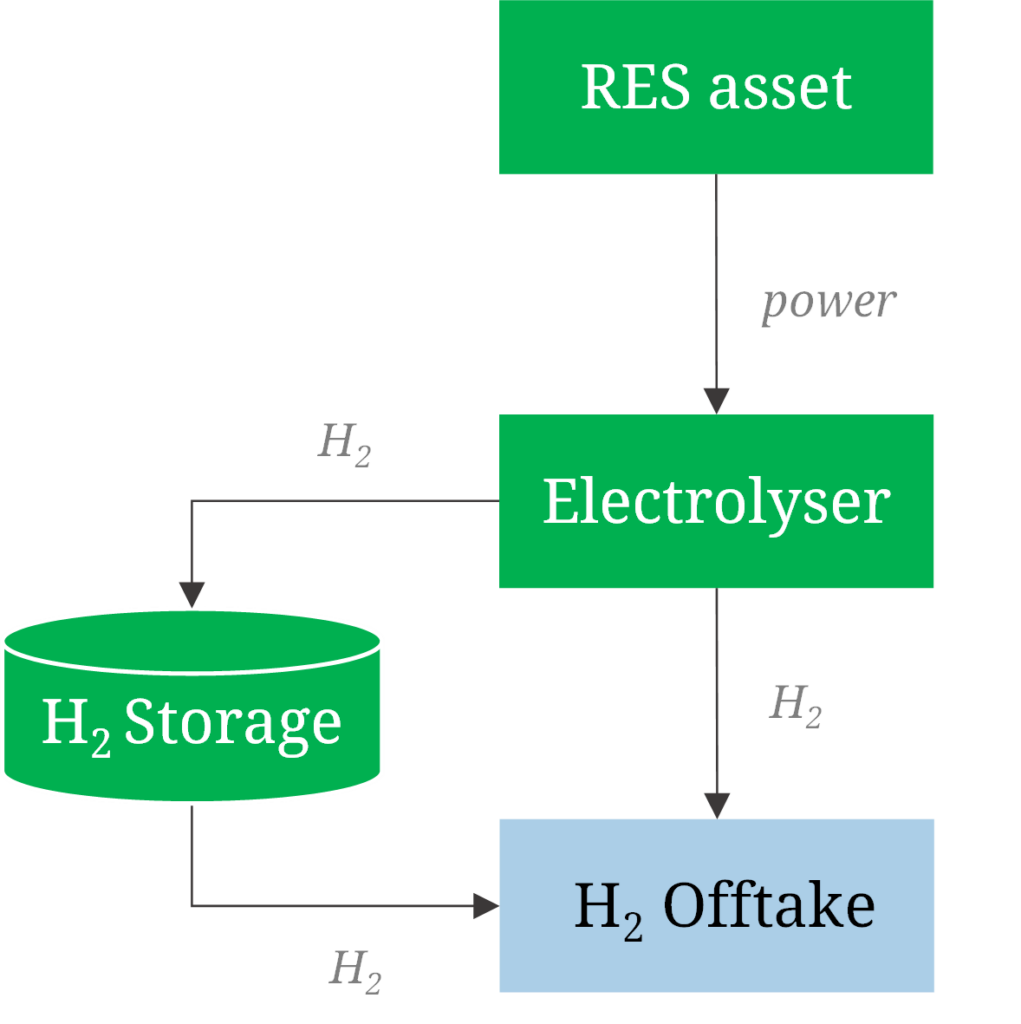

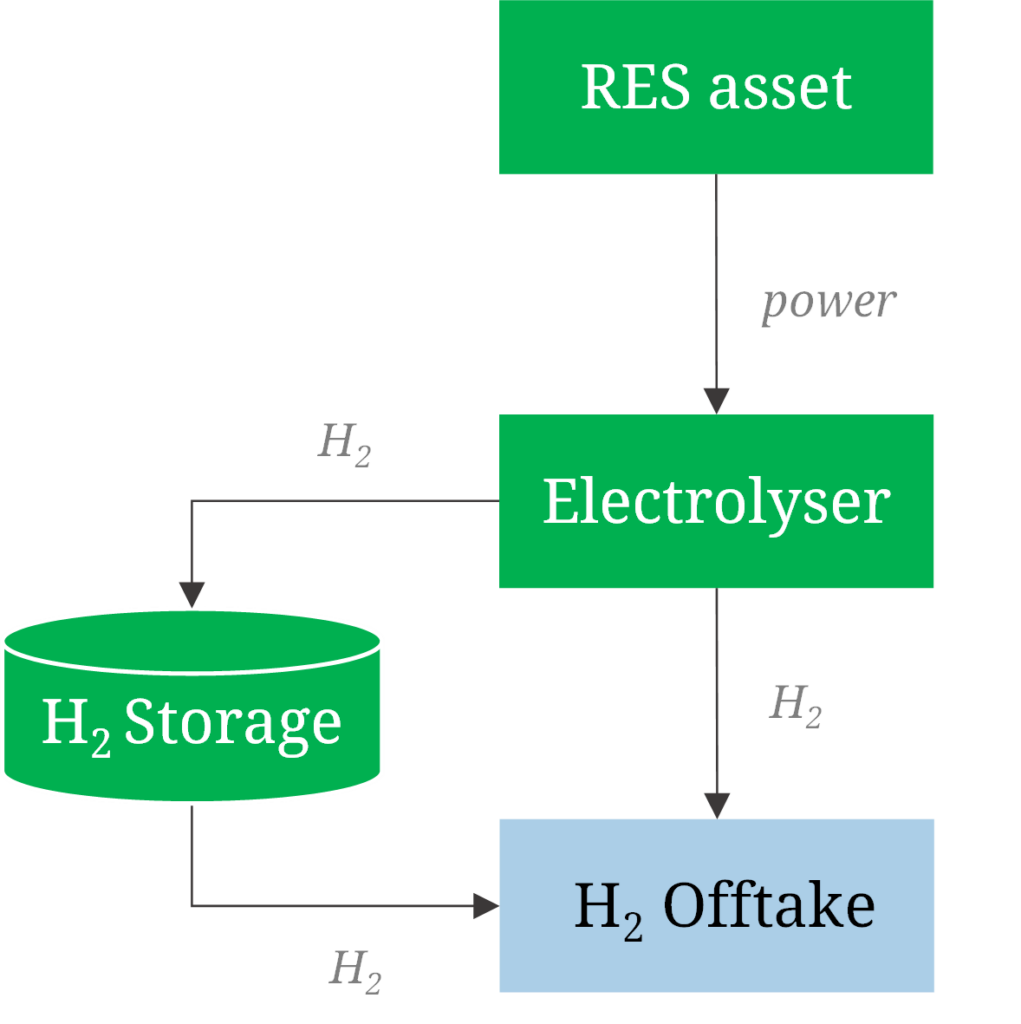

Model 1: Direct RES

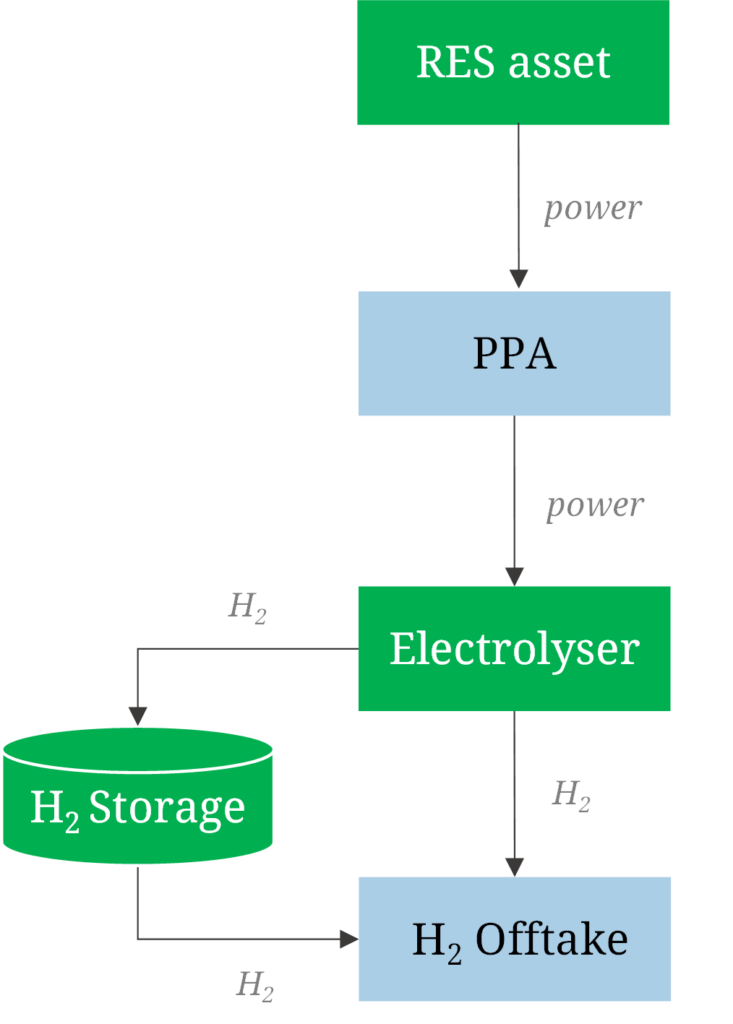

Under this model the electrolyser sources its green power directly from a RES asset (e.g. wind or solar farm) as shown in Diagram 1. In almost all cases the RES asset and electrolyser are also connected to the power grid. But to comply with ‘green power’ sourcing rules, the electrolyser needs to be operated flexibly to ‘match’ the output profile of the RES asset (albeit only at a stricter hourly granularity from 2030).

This model is relatively simple and creates an integrated supply chain. But it also creates a dependence of electrolyser production on the generation output profile of the RES asset – this is a big deal when hourly ‘matching is introduced from 2030. Tying H2 production to RES output profiles constrains electrolyser production flexibility. This can act to significantly drive up H2 production costs, harming project economics & competitiveness.

This issue can be partly addressed by:

- Oversizing of the RES asset to ensure a more reliable supply of green power to the electrolyser; although this creates additional power market exposure from the requirement for the merchant sale of surplus RES production not used in the electrolyser.

- Developing onsite H2 storage that allows delinking of electrolyser production from offtake delivery, which can provide substantial value uplift. The same principle can be achieved via installing a battery on the renewable site, but this is typically a more expensive solution than H2 storage.

- Where possible, passing risk on via the H2 offtake contract structure.

The main challenges with this simple direct RES model are (i) competitiveness versus more dynamic sourcing models and (ii) the risks/costs associated with RES oversizing.

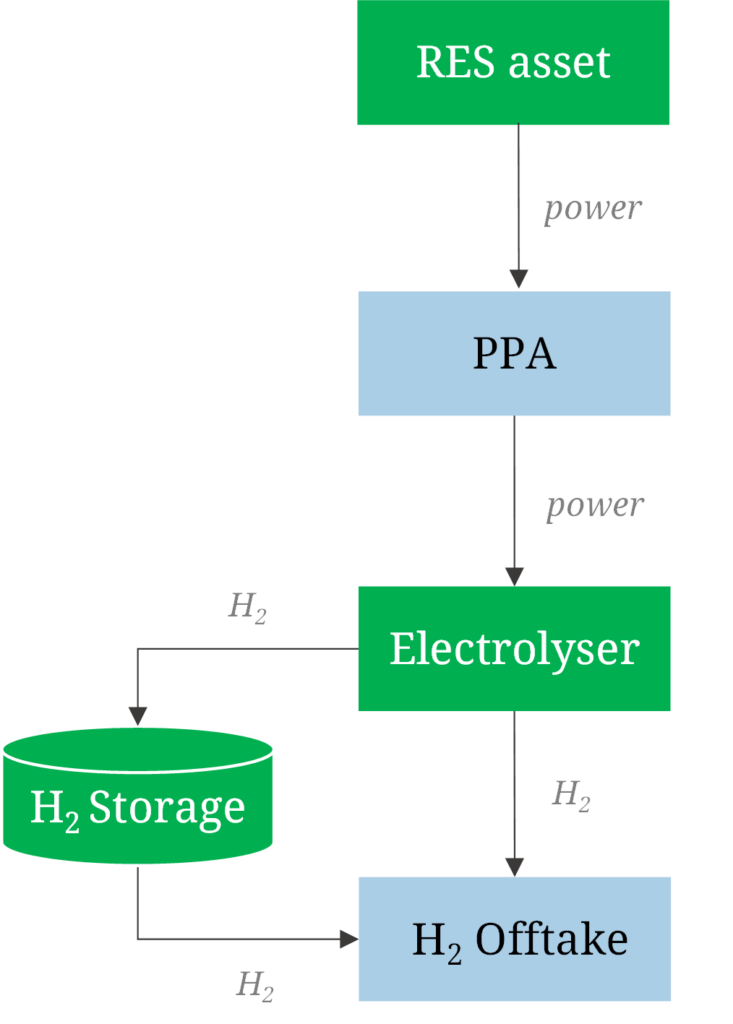

Model 2: RES PPA

Under the second model, the electrolyser sources power via PPA from one (or more) RES assets located in the same bidding zone as the electrolyser, as shown in Diagram 2.

Diagram 2: RES PPA sourcing model

As for model 1, electrolyser production depends on the production profile of the RES asset, but the PPA enables geographical separation between the electrolyser and the RES asset site.

This separation can significantly reduce project costs if it enables the electrolyser to be located near to the offtake site, because it minimises H2 transport infrastructure requirement. The oversizing and H2 storage options we set out for the Direct RES model also apply here.

The other benefit of the RES PPA approach is that it can reduce exposure of the electrolyser project to RES costs/risks.

The challenge for this approach is the requirement to sign a long term fixed price PPA that enables competitive H2 production. The PPA fixed price risk also needs to be managed via the H2 offtake agreement to develop a bankable project.

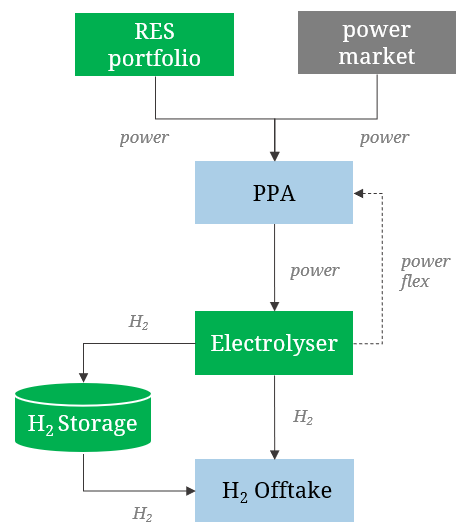

Model 3: Structured PPA

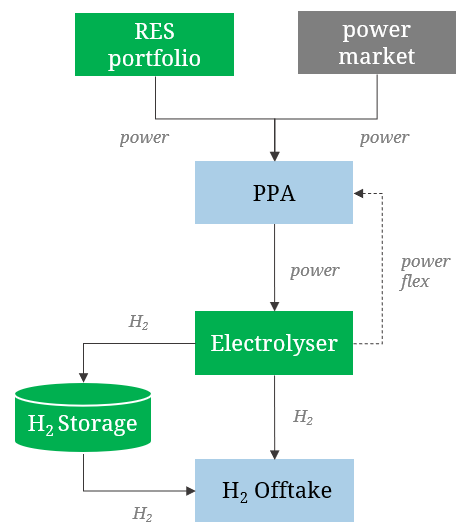

The third model involves a structured PPA contract with a trading counterparty (e.g. utility or trader) which can more dynamically manage green power sourcing across its RES portfolio (including own assets & PPAs) and the power market, as shown in Diagram 3.

Diagram 3: Structured PPA sourcing model

Advantages of a structured PPA approach include:

- Ability to provide a significantly more flexible and lower cost green power supply into the electrolyser via sourcing from a combination of:

- pooled own portfolio RES assets or PPAs

- low wholesale market prices (i.e. power under the 20 €/MWh or 0.36 * EUA cost thresholds)

- Guarantee of Origin backed 3rd party RES.

- Greater price & volume flexibility vs a standard RES PPA (reducing cost & risk)

- The ability to receive additional revenue by allowing the PPA counterparty to use electrolyser flexibility to provide power market flex services.

This model has a more bespoke PPA contract structure, but has the potential to unlock substantial benefits in reducing H2 production costs & project risks, as well as increasing revenue potential.

A variation to this model is that the electrolyser owner signs a tolling agreement with a 3rd party trading counterparty (for a fixed capacity fee), which then manages power supply & offtake contracting as well as optimising the electrolyser production profile to maximise value.

Comparing the 3 sourcing models

In the work we are doing supporting hydrogen investors structure PPA & offtake contracts, we are consistently seeing projects under-estimate the potential value & risk benefits of alternative power sourcing strategies. So let’s finish by summarising the advantages & disadvantages of each of the 3 power sourcing models in Table 1.

Table 1: Summary of 3 green power sourcing models

Note: there are many variations on the 3 models we set out above. These include hybrid approaches that incorporate different elements of these models and tranching of power sourcing.

Getting power sourcing right

Hydrogen is by nature an expensive energy source because of the efficiency losses from energy conversion. The competitive viability of green hydrogen projects therefore depends on securing low cost green power.

Integrating an electrolyser with a RES asset may be the simplest approach. But it can impose substantial costs & risks on a green hydrogen project.

A range of potential sources of green power, from different RES assets and the wholesale market, underpin the potential benefits of a more dynamic power sourcing strategy. Effective contract structures for both PPAs and H2 offtake are a key source of competitive advantage and project risk mitigation.