There are some major energy related misconceptions gaining traction in Europe. These are being driven by a strong political narrative that Europe will steer a rapid path to independence from Russian gas.

“It has never been more important to analyse the difference between what is promised vs what is possible”

The EU has announced its intention to reduce its dependence on Russian gas to zero by 2027, targeting a two-thirds reduction by the end of 2022.

The political motivation here is compelling. Europe pays more than €100bn a year to Russia for energy imports. These payments are funding the enemy at our gate. There could not be a stronger incentive for Europe to reduce Russian energy imports.

However the path to energy independence from Russia needs to be grounded in the practical reality of where alternative gas supply will come from. The political solution is focused on LNG. Market price signals are shouting loud & clear that the EU’s approach will not facilitate an orderly transition from Russian gas.

European hub prices surged last week after Gazprom cut supplies through the key Nord Stream 1 flow route by 60%. This renewed market stress comes as a warning of how difficult an orderly near term transition from Russian gas will be.

In today’s article we set out some numbers behind Europe’s challenge to wean itself off Russian gas.

The reality about demand reduction

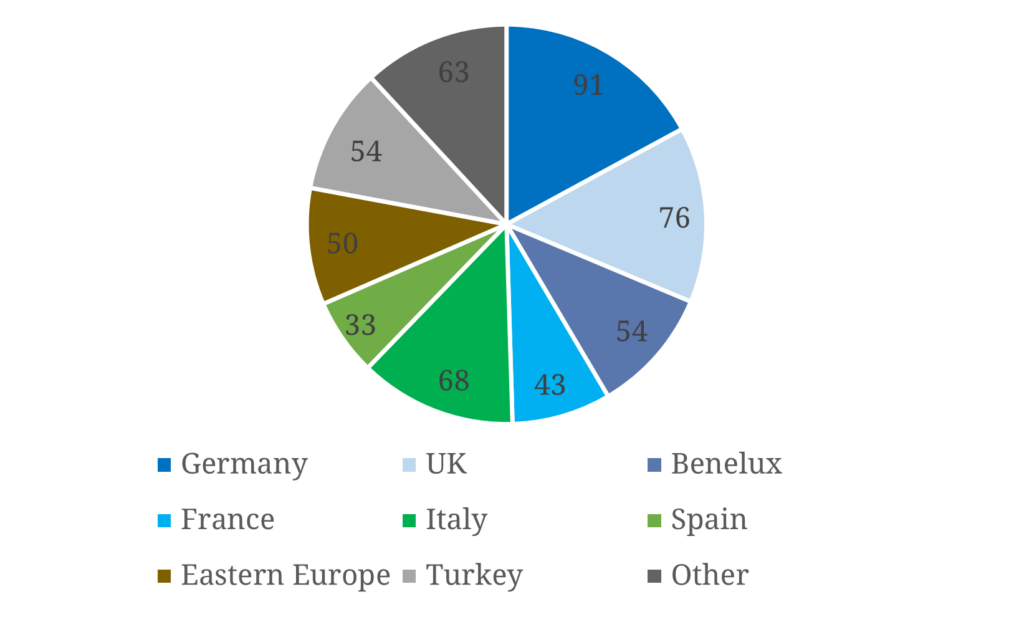

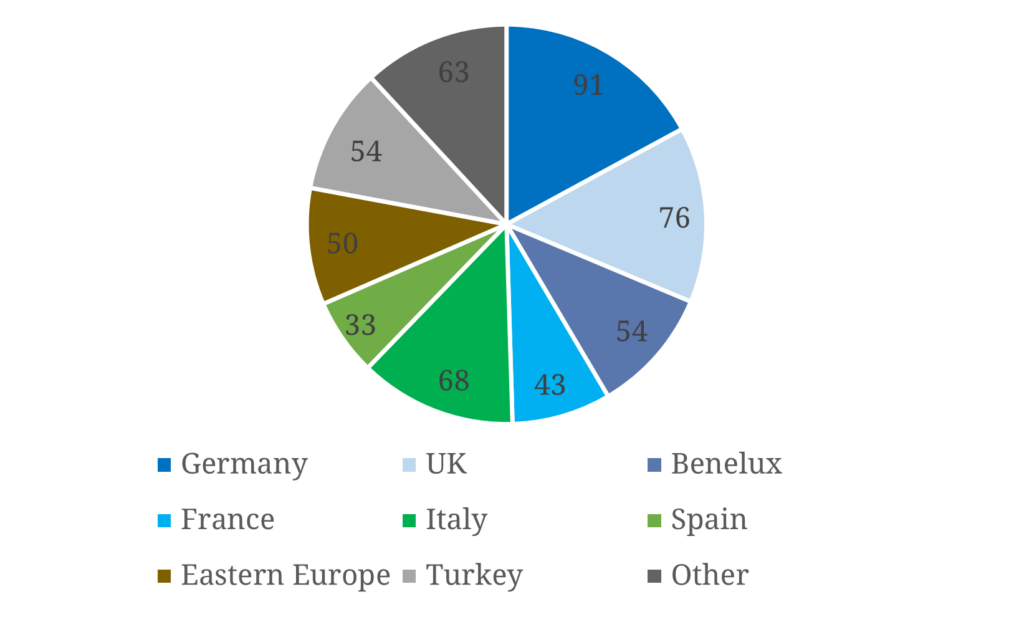

European gas demand was 532 bcm in 2021 (including UK and Turkey). Chart 1 shows the breakdown of demand by country/region.

Chart 1: 2021 European gas demand by country/region (bcm)

Source: Timera Energy, IEA

European gas demand in 2022 to May is tracking around 9% lower year on year vs 2021. At a headline level this is quite an impressive reduction, but there are some important reasons we set out below as to why it may not be sustained across the rest of the year or into future years.

Heating: Reduction in heating demand in 2022 has been a major factor in reducing gas demand vs 2021. 2022 weather has been relatively mild vs colder temperatures in early 2021. This mild weather effect does not represent a structural reduction in demand in response to policy or price. And it could reverse next winter. There is not much clear evidence so far of material heating demand reduction from consumers voluntarily turning down thermostats.

Power: Power sector gas demand has fallen in early 2022 vs early 2021. However this reflects gas to coal plant switching given the huge increase in gas prices in H1 2022 vs H1 2021. Europe’s power sector is now fully switched (coal running at full output) and looming nuclear & coal closures mean further reductions in power sector gas demand will be challenging (with the potential for temporary increases).

Industry: There is some clear evidence of industrial demand destruction in 2022 given high prices. That may increase in future if prices rise further or gas rationing measures are imposed. But this comes at the economic cost of destroying industrial demand.

Storage: Storage inventories were drawn down heavily in 2021. Countries across Europe have imposed minimum storage inventory mandates in 2022. Both these factors are set to drive stronger than normal storage injection demand this year.

What is required to structurally reduce demand?

Material further reductions in gas demand require (i) implementation of practical policy measures to incentivise or force reduction and (ii) substantial incremental investment to enable transition to alternative sources of energy.

Key areas flagged in the EU’s recent Repower EU strategy release include:

- Further accelerating renewables deployment

- Deploying more heat pumps

- Tightening building standards e.g. insulation.

All of these solutions make sense but face major policy, planning and investment hurdles. They also typically have long lead times (years not months).

The other alternative is further gas demand destruction via higher prices. But Europe is already facing a dual economic challenge of surging inflation and rapidly slowing growth. Further rises in energy prices act to accelerate both. This represents the political path of maximum resistance given increasing concerns on inflation & the economy.

The reality about supply substitution

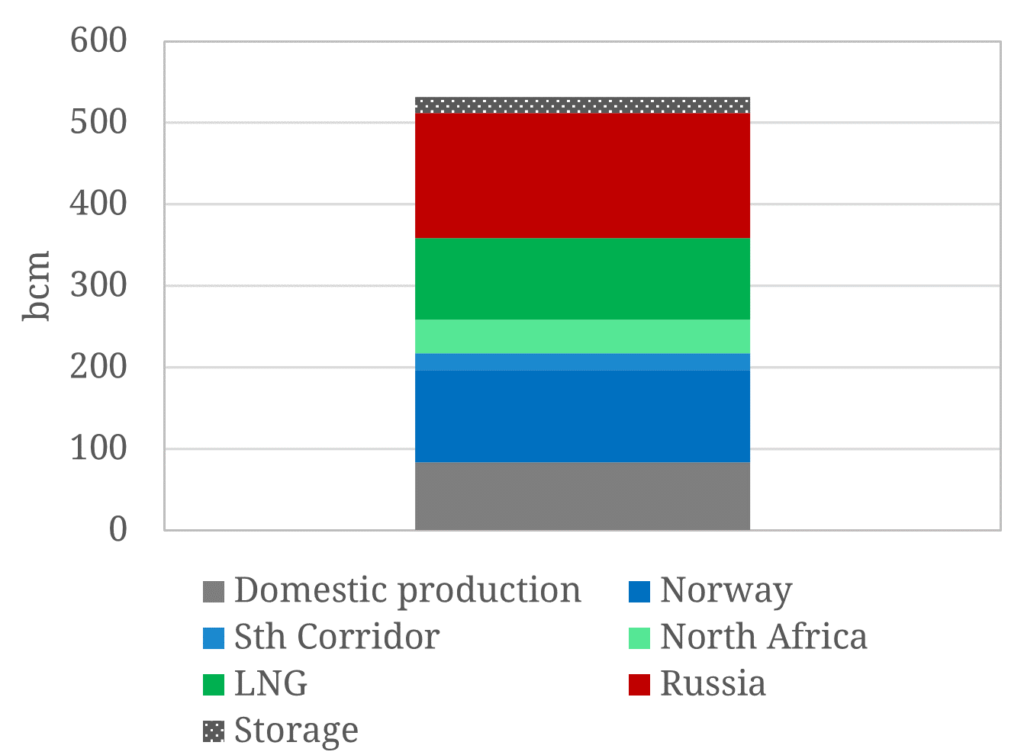

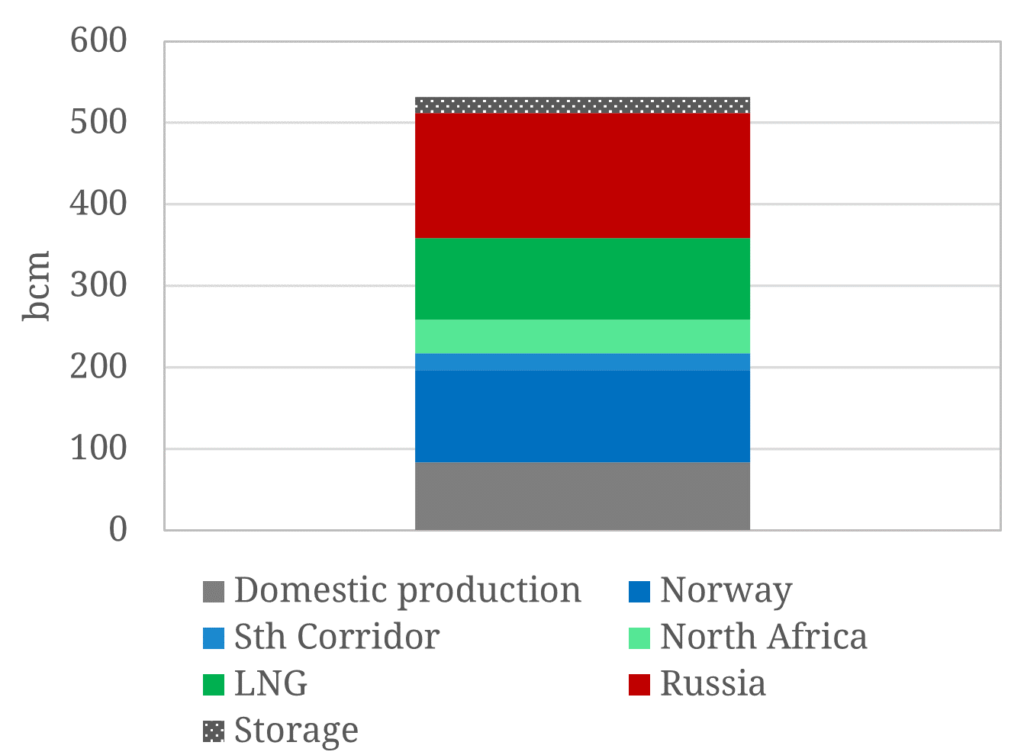

Europe imported 154 bcm of gas from Russia in 2021. This made up 29% of total European gas supply as shown in Chart 2.

Chart 2: 2021 European gas supply by source (bcm)

Source: Timera Energy, IEA

There are only two ways to reduce Russian gas imports while balancing the European gas market (ignoring within-year storage balances):

- Reduce European gas demand (see challenges set out in the section above)

- Replace Russian supply with gas from other sources.

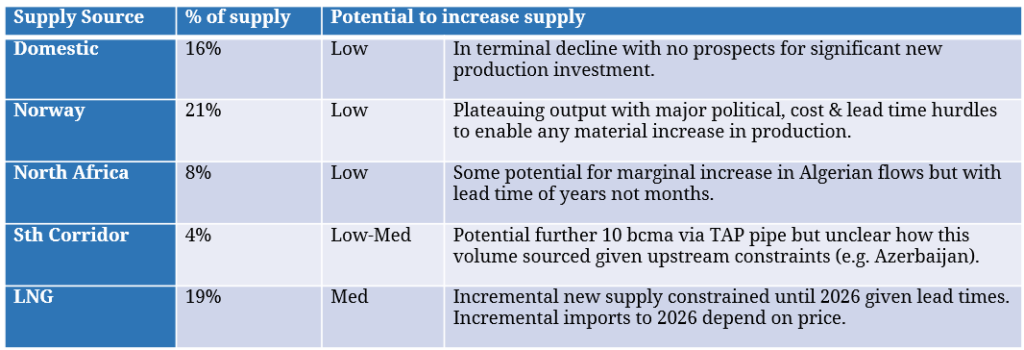

The table below sets out the key categories of non-Russian gas supply, 2021 % supply contributions & potential to increase supply across the next 5 years.

In summary:

- 1 year horizon: Material increases in non-Russian supply in 2022 are firmly focused on LNG. Storage mandates make this year even more challenging given incremental injection demand. The US Freeport LNG terminal fire will also reduce available exports in 2022.

- 5 year horizon: Some incremental supply gains may be possible from North Africa (mostly Algeria) & Sth Corridor (Azerbaijan) but are likely limited. Incremental supply is therefore also focused on LNG.

Both this year and across the next 5 years, Europe is relying primarily on a pivot to LNG to enable reduced dependence on Russian gas.

The inconvenient reality about LNG

There is a 4-5 year lead time to bring on new LNG supply. That means new investment in LNG supply that has been triggered by Europe’s pivot from Russian gas to LNG will have no impact until 2026 at the earliest.

In the meantime Europe will need to battle with Asia & Latin America for any incremental LNG supply to facilitate reduction of Russian pipeline imports. That means higher prices as we saw last week with the reduction in Nord Stream 1 flows causing the front of the TTF curve to surge 70% (above 140 €/MWh) with Cal 2023 prices breeching 100 €/MWh, before prices retraced some of those gains on Fri.

Europe is purposefully trying to secure additional regas capacity and sign new LNG supply contracts, as well as address several key transmission bottlenecks. But the battle for available LNG is close to a zero sum game across the next 4-5 years. The only way Europe can attract higher LNG imports is to drive market prices up an inelastic supply curve, to create demand destruction in Asia or Latin America.

Europe currently depends on Russia for 154 bcma (112 mtpa) of imports. It is very difficult to define a credible scenario where that volume goes to zero in the next 5 years.

To attempt to replace even half of that volume with incremental LNG imports would likely drive gas prices much higher up an inelastic global supply curve. This could only be achieved via triggering large scale industrial demand destruction in Asia.

European producer price inflation is already running at 30% year on year. Consumer price inflation is also accelerating. The European Central Bank was forced into a hawkish pivot this month as it tries to stave off stagflation.

If there is a path to rapidly reducing Russian gas dependence without inducing further inflation and a severe energy price induced recession… we can’t see it (in the absence of fiddling the numbers).

What are the implications?

It is easy to be cynical in the face of enormous challenges. That is not the purpose of this article.

Many elements of the European policy course away from Russian gas make sense from both a strategic & decarbonisation perspective. Gazprom’s flow cuts on Nord Stream 1 last week represents what appears to be a further weaponisation of gas flows targeting the European economy. But words need to be underpinned by tangible policy actions and realistic timelines.

What are the implications for energy investors and asset managers? There has never been a more important time to analyse the difference between what is promised vs what is possible. And the scale of political & market uncertainty is set to structurally increase the cost of capital invested in energy assets.