There was much excitement last month when EnBW and Dong bid to deliver 1.4GW of ‘zero subsidy’ offshore wind projects in the 2017 German offshore wind auction. Grid connection costs for these projects will be borne by German consumers. But the developers will need to recover the remainder of costs from wholesale power price revenue alone.

A case of return free risk? Maybe. But the auction results point to two interesting dynamics:

- Continuing reductions in offshore wind technology and implementation costs.

- Germany’s focus on wind as the main source of replacement capacity for closing nuclear and thermal power plants.

These dynamics have important implications for the German power market balance, given large volumes of scheduled thermal and nuclear capacity closures over the next 5 years. They are also important for the broader pan-European market balance, given the size of the German market and tightening reserve margins in neighbouring markets.

Looming German capacity closures

To date the German power market has absorbed new wind capacity in a relatively orderly fashion, although system stress points are starting to show. The transition to higher volumes of wind output has been helped by a large buffer of flexible gas, coal and nuclear capacity and high volumes of interconnection with neighbouring markets.

But the German power market faces a new challenge over the next five years. Not only will Germany continue to add large volumes of intermittent renewable capacity, it will also lose large volumes of flexible coal and gas and baseload nuclear capacity. And market price signals do not currently support adequate returns on existing thermal plants, let alone investment in new flexible capacity.

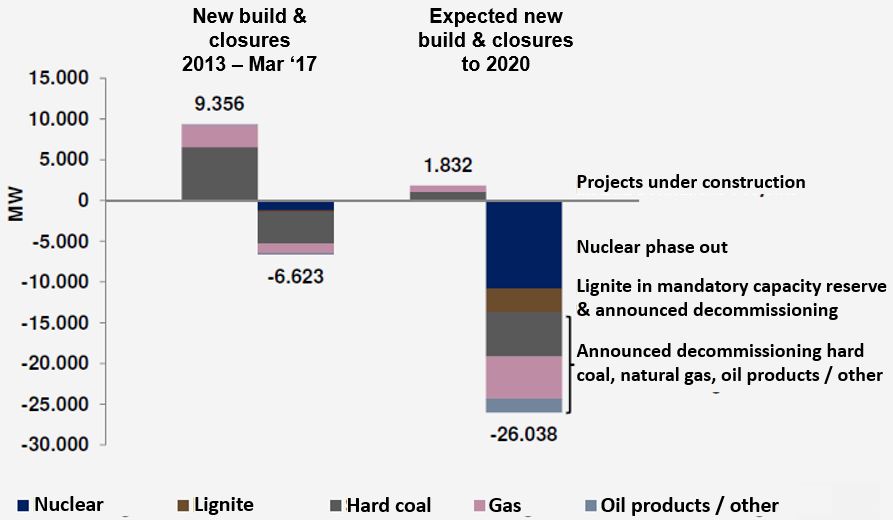

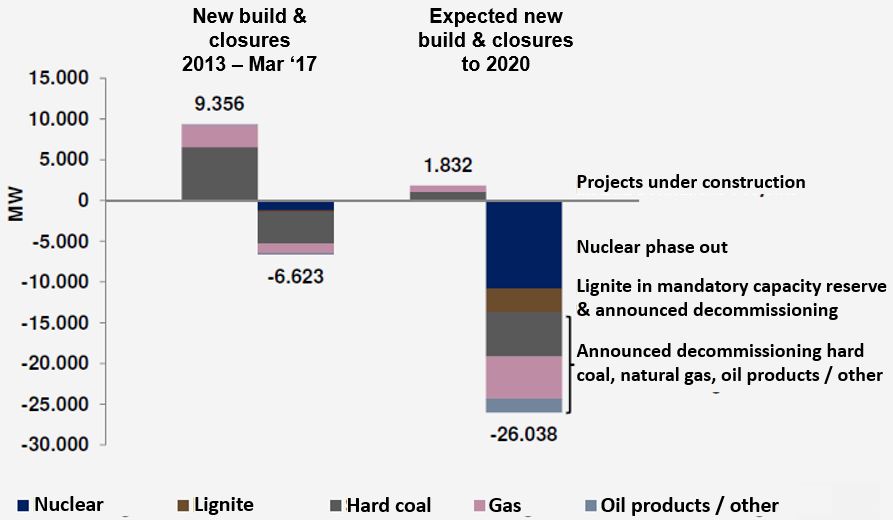

The plant closure issue Germany faces was highlighted recently by BDEW (the German Association of Energy and Water Industries), who are projecting 26GW of German capacity closures by 2022 as shown in Chart 1.

Chart 1: Recent and projected German conventional capacity new build and closures

Source: BDEW (translated)

While the BDEW projection may somewhat over estimate closures, the chart illustrates an important point. The German market saw a net addition of 3.3GW of flexible capacity over the last 5 years (2013-17). But it is confronting a very substantial net deficit of flexible capacity over the next 5 years (BDEW estimates 24GW of net closures), given a lean development pipeline of non-renewable capacity (1.8GW).

Capacity closures are being driven by two main factors:

- 11GW of regulatory driven closures of German nuclear plants by 2022.

- Ongoing closures of coal and gas fired plants as a result of more stringent emissions requirements and weak generation margins.

We recently showed the very low levels of prevailing spark and dark spreads in the German market. Spark spreads have been negative for more than 5 years, with dark spreads hovering near zero for the last 18 months. This has crushed returns on coal and gas fired generators, resulting in an ongoing flow of announcements by plant owners of their intention to close capacity.

So far the German electricity regulator (BNetzA) has been notified of a total of 13.3GW of thermal capacity closures. Of this volume 5.7GW has already closed. Another 7.6GW is awaiting closure, although 3.3GW of this is required to remain open for security of supply reasons (e.g. relating to constraints in the South of Germany).

The implications of swapping baseload capacity for wind

Germany has close to 55GW of installed wind capacity. Average wind farm load factors range from 20% for onshore projects to more than 40% for advantaged offshore projects. As Germany continues to rollout wind capacity, this contributes significant additional generation output on an annual average basis.

But it is periods of low wind & solar output that are important for German security of supply. System continuity depends on a buffer of adequate flexible capacity to meet peak demand in periods of low wind generation. And this is where capacity closures leave the German market exposed, a fact that is being disguised by complacency driven by a number of years of over-capacity.

Germany’s gradually increasing security of supply exposure was illustrated over the past winter when renewable contribution to the German market stagnated. For a two week period renewables contributed little more than 3GW of capacity through a period of higher winter demand. In these circumstances Germany relies heavily on imported flexibility, for example from hydro capacity in Scandinavia and the Alpine regions. This cross-border dependence means that swings in German renewable output are also forcing unwelcome stress on neighbouring transmission systems.

Investment in replacement flexible capacity?

Germany has not implemented any form of market wide capacity payment mechanism. So as renewable output grows, margins on coal and gas fired power plants will continue to be eroded by lower variable cost units setting marginal prices. In this environment it is hard to see how significant volumes of new CCGT capacity will be developed without capacity payment support.

Germany has so far instead been pursuing a capacity reserve policy The proposed approach involves network operators initially procuring and holding 2GW of reserve capacity outside the wholesale market from Winter 2018.

But last month the EU raised a number of state aid concerns relating to the German reserve scheme (e.g. it is not open to foreign capacity or DSR). The German approach is not helped by the fact that grid operators are playing an increasingly interventionist role after the day-ahead auction has cleared, causing growing divergences in real time pricing and dispatch.

In our view, pressure on thermal generation margins may precipitate a capacity crunch sooner than expected in Germany. If the regulator does not provide a clean answer, the market will. This could have a significant knock-on impact across North-West Europe as reserve margins also tighten in neighbouring markets (e.g. France and Belgium).

The UK’s experience with its Supplementary Balance Reserve (SBR) policy suggests that piecemeal capacity reserve schemes are a mistake. Germany would be better anticipating the requirement for a competitive, technology neutral, system wide capacity market, well in advance of a system capacity crunch.

Authors: David Stokes & Olly Spinks