This is the second in a series of articles on the principles of energy risk management, written by Nick Perry.

In the previous article we considered a range of common misconceptions about risk management in energy companies, not least of which is the notion that hedging is trivial for portfolios not containing options, i.e. for exposures with linear ‘delta’. (Did you solve the two-minute challenge?)

In this second article we are again putting options aside for now, to focus on ways in which even basic risk management for energy is more demanding than for other commodities. In most cases the reasons stem from fundamental characteristics that will not change or improve over time. We take a look at some of the important risk management implications of these characteristics in the form of volatility, volumetric risk and basis risk.

Volatility

When natural gas became a traded commodity for the first time, levels of volatility were encountered that re-wrote the game-book on what constituted high volatility. For example it is not unusual for spot gas volatility to rise to levels above 100% on an annualised basis, around 10 times greater than spot foreign exchange volatility. When power started to be traded some years later, the books were revised again: electricity is the most volatile commodity ever traded. Spot power volatility can rise to levels above 1000% (annualised).

The reasons are clear, and will not change any time soon. These commodities are extremely ‘granular’: gas portfolios must be balanced daily and power in real-time; and storage of both is difficult – in the case of electricity, quite exceptionally difficult. These factors will drive considerable volatility in spot markets for as long as they persist which, being based on the laws of physics, will be for the foreseeable future. And almost every aspect of risk management is made more problematic by high volatility.

Volatility is a key driver of the value of asset & contract flexibility. As a result there is an important relationship between volatility and energy portfolio risk, given the inherent flexibility of most energy portfolios. Flexibility can be considered in two categories: owned flexibility (e.g. upstream production flex, gas storage capacity, power plant) and sold flexibility (e.g. gas swing contracts, retail power contracts). Effectively managing sold flexibility exposures against underlying asset positions in energy portfolios, is one of the key challenges of energy risk management (given high price volatility) and one we return to in more detail later in this series.

Volumetric Risk

In most commodities, the volumetric aspects of a deal are unremarkable. I buy 10,000 tonnes of steel, and that’s what is delivered. But when I enter a contract for gas and power, as an end-user I will very rarely be able to specify the amount I will buy. On the coldest day in winter, will I turn on every heating appliance in the house – or will I go on a skiing vacation and use nothing? Or cancel my contract and switch suppliers?

It is not just retail portfolios that suffer from volumetric uncertainty. Demand for gas and power are remarkably sensitive to ambient temperature; and power plants can trip at any time: just two of the many vicissitudes of the sector. In systems that must balance in real-time, such uncertainties – often termed Volumetric Risk – present very complex challenges (and, incidentally, contribute significantly to the volatility mentioned above). Once again, this problem is far more acute in energy than in any other commodity.

Take the prompt exposures of a vertically integrated power portfolio as an example. The portfolio needs to be broadly balanced in real-time to avoid exposures to very volatile prompt and balancing prices. Volumetric risk in the portfolio stems from the flexibility sold to customers via retail contracts. Customer load may swing substantially over short periods (e.g. given changes in weather conditions). Given short term market liquidity constraints, this exposure is often managed via ownership of flexible power plants (e.g. gas peaking assets). However forced outages on generation assets can add to the complexity of volumetric risk, given that these may leave wholesale contract and retail positions exposed to volatile prompt prices.

Basis Risk

Basis risk – where the variability of the value of an underlying exposure is not perfectly inversely correlated with that of its hedge – can be an issue in any portfolio. But in energy there are more twists than usual. In particular:

Delivery point: the complexities of transportation for gas and power, and sometimes also coal and even oil, mean that end-users and smaller wholesale players are often uncomfortable with taking settlement at one of the handful of delivery-points at which hedges are most readily found, which may be a long way from their ‘natural basis point’. Thus, locational basis is a very common issue in energy markets.

For example, liquidity in European coal is focused around API2, a specified set of conditions for delivery of coal to Amsterdam- Rotterdam-Antwerp (ARA). Yet many owners of European coal-fired plant use API2 contracts to hedge coal delivery to locations which are separated both geographically and logistically from the ARA area.

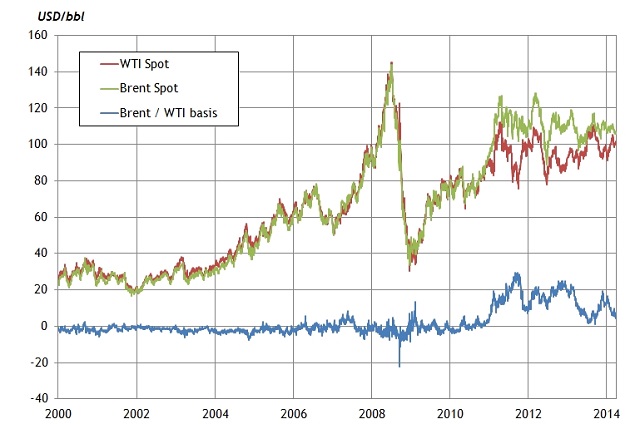

Quality / specification: there are very many grades of oil and coal, but hedges only exist for a handful of grades. The well-traded hedging grades will for the most part be highly correlated with other grades, but not perfectly so: and small differences multiplied by large volumes over long periods of time can add up – particularly for the many energy players operating a margin business model, such as refiners, thermal generators and retailers.