The uncertainty surrounding Brexit is a breeding ground for theories and threats. There are some genuine economic risks posed by Brexit that may have a knock on impact on energy markets. But some increasingly exaggerated claims are circulating as to the direct impact of Brexit on the UK gas market.

We are particularly sceptical about the ideas that:

- “Trade barriers will be imposed on gas”

- “A major shift in gas regulatory policy will take place”

- “The UK’s gas security of supply will be compromised”

- “UK hub liquidity will disappear”

We look at the potential implications of Brexit in these four areas in today’s article. This is also directly relevant to the UK electricity market, given the importance of the UK gas market as a driver.

UK gas trade barriers

In terms of the UK’s future trade & economic relationship with the EU, the two most likely outcomes appear to be either:

- A negotiated trade deal: which (from the EU side) would be inferior to the terms of EU Membership, and from the UK side would have to be more attractive than the WTO option

- The WTO default option: which provides a ‘floor’ above which an eventual negotiated settlement can be measured on the basis that ‘no deal is better than a bad deal’.

Several industry and media sources have raised the prospect of new tariffs being placed on gas flowing between the UK and EU Member States (Ireland, Netherlands, Belgium) and by extension Norway (an EEA/EFTA Member). Notwithstanding a possible political desire to ‘punish’ the UK (‘pour discourager les autres’), this is a poorly constructed argument on several levels.

The purpose of a tariff is to protect and incentivise ‘domestic’ production by making imports more expensive. But both the UK and continental Europe in aggregate are net importers of gas. Therefore it makes eminent sense for the UK and EU parties to encourage the efficient sharing of gas. In the case of the UK and North West European regions the same logic applies to gas flows. Given both regions have liquid gas trading hubs, flows should respond to price with minimal tariff barriers.

The UK is a large export market for Norwegian gas (supplying some around 37% of UK requirements in 2016). Furthermore the pipeline infrastructure from Norway to the European continent has insufficient capacity to take all Norway’s output. Norway would be unwilling to be penalised by having a tariff charged on its pipeline exports to the UK and lose out to LNG imports paying nothing.

But the situation is more complicated than this. With the closure of Rough storage, flows between the UK and NW Europe are set to become even more seasonal. This means higher exports from the UK in summer as LNG imports and Norwegian gas, surplus to the UK’s immediate requirements, seek storage capacity in onshore North West European facilities. In the winter, the UK will receive higher flows from NW Europe (storage withdrawals, Dutch production and Russian pipeline flows).

The imposition of tariffs on gas flows in both directions between the UK and the Continent would benefit the respective governments of Belgium, Holland and Norway (and the UK if it chose to retaliate with a tariff charge on imports from the EU and EEA). But tariffs would create periods of dislocation between TTF and NBP, probably partially ameliorated by LNG arbitrage. Norway would still need to send considerable volumes of gas to the UK as its pipeline delivery system to the Continent is close to capacity in winter months with high volumes to the UK.

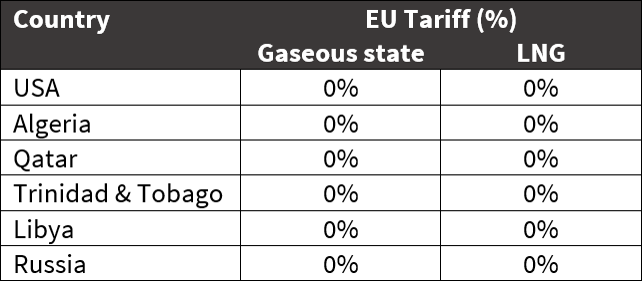

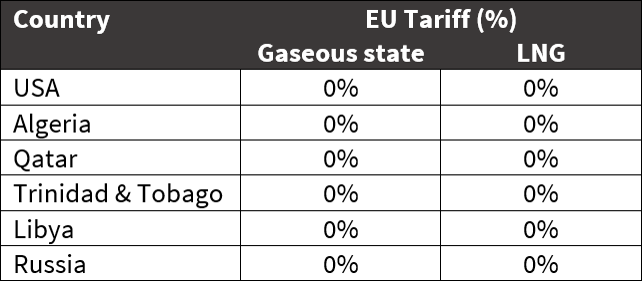

Before going further down this road of speculative cause and effect, it is worth asking if this is really a likely outcome? We can shed light on this question by looking at the tariffs imposed by the EU to a range of non-EU member countries in Table 1.

Table 1: EU tariffs on non-EU member countries

Source: EU Tariff Tables (Code: 2711)

With the EU a long-time net importer of pipeline gas and LNG it is perhaps no surprise that it imposes zero tariff on imports.

So if there was to be a post-Brexit tariff imposed by the EU on imports/exports of gas with the UK, it would likely be in the context of a ‘punitive’ deal offered by the EU to the UK. In this outcome the UK may (as has been stated as its ‘negotiating position’) opt for ‘no deal’ and a default to WTO terms.

What does the WTO have to say about gas trade tariffs ? Inspecting the WTO database it is clear that the EU applies no tariffs to either natural gas or LNG under WTO terms.

Given the above it is reasonable to conclude that there is little if any prospect of post-Brexit tariffs being applied to gas flows between the UK and the EU/EEA.

Gas Regulatory Framework Development

The EU on the European continent lagged the UK in liberalising its gas markets by several years. Although the development of EU gas market regulation was based on a ‘from first principles’ approach, the active involvement of interested UK players ensured that ‘lessons learned’ from the UK experience were incorporated. This has led to the UK and EU being reasonably harmonised on gas regulation, with the exception of those continental member states who have been slow to adopt some regulatory packages in full.

UK interests and policy to date clearly support free unimpeded interflow of gas with the European continent in response to hub price signals. As a result it is reasonable to expect that UK regulatory authorities (and industry participants) will continue to broadly comply with future regulatory developments.

Gas Crisis/Security of Supply Management

A set of Draft Security of Supply Regulations published in 2016, shed some light on the EC’s approach to a major supply disruption. The key principle is that in the situation where a key European gas supply source is cut off, the allocation of supply would be taken over ‘by committee’. This approach might conceivably work in some specific cases, for example a group of East European markets with no trading hubs, state monopoly system operators and suppliers/distribution companies and one or two sources of cross border imports. But it seems inapplicable to the liberalised gas markets of NW Europe.

In a supply crisis a ‘committee of the great and good’ on the above model would have to:

- Suspend trading on TTF or other liquid hubs (and potentially compensate for losses/declare force majeure)

- Take over the control of flows into or out of the bloc of countries forced to share supply and optimise the distribution to customers on a merit order basis, as well as regulating a storage drawdown

- Presumably impose a wholesale and retail price controls to guard against speculation.

What seems more practical is the present system of national response, where the system operator intervenes to shed industrial demand in the face of a supply shortfall. The price signals between hubs in northwest Europe will perform a faster and more efficient job of allocating supply and storage withdrawals than any committee (as shown by the Russian gas supply crisis in February 2012). The exclusion of the UK from this framework post Brexit in practical terms is immaterial. Even if invoked it would be unworkable.

Nevertheless this leaves the EU member state of the Republic of Ireland in a seemingly vulnerable position. It has recently brought onstream the much-awaited Corrib offshore field which for a few years may cover some 60% of domestic demand. However the balance is imported from the UK.

Once the Irish Kinsale Head and Seven Heads gas fields commenced decline, imports from the UK met the balance of Ireland’s requirements from 1995 to the present day. Against the backdrop of UK taxpayers bailing out Irish banks after the financial crisis to the tune of £14bn with no popular dissent, it is inconceivable that the UK, post Brexit would fail to supply Ireland with gas (via pipeline interconnectors). Even without the Corrib Field, this is only 5 bcma, just 6% of UK consumption.

NBP vs TTF hub dynamics

The biggest practical impact of Brexit on the UK gas market may be its impact on relative pricing and liquidity of the UK NBP and Dutch TTF hubs.

The key differences between these two hubs are:

- NBP is sterling denominated; served by (declining) UK production, Norwegian imports and some 48 bcma of LNG import capacity.

- TTF is Euro denominated; served by (declining) Dutch production, Norwegian imports, Russian imports and 12 bcma of LNG capacity in the Netherlands (plus 9 bcma in Belgium).

In recent years TTF has been in the ascendancy, overtaking NBP in terms of total trading volumes. TTF also now has a futures curve at least as liquid, and therefore useful for risk management, as the NBP. Brexit will likely support a continuation of that trend, particularly given the additional risk associated with GBP exchange rate volatility post Brexit.

But this does not mean that UK gas market liquidity is going to disappear. The recent move to merge the TTF hub and BBL pipeline to cut the cost of the Dutch-UK gas flow illustrates that both hub areas are deemed to be important. It also demonstrates that the view that the UK will be ‘cut off’ from the Continent post Brexit does not seem to be shared by key players. This is reinforced by the UK’s role as a desirable destination for LNG cargoes given substantial regas capacity and liquid market access.

Instead of disappearing, the UK NBP is evolving into a ‘satellite’ hub to TTF. European gas prices are anchored by the TTF hub in EUR terms. NBP prices then reflect any EUR-GBP exchange rate movements (which create additional NBP volatility) as well as the variable transport cost differential to TTF. Major NBP and TTF divergence typically only takes place during periods of interconnection constraints. It is market forces that will dominate the evolution of NBP and TTF, not Brexit related regulatory intervention.

Article written by David Stokes & Olly Spinks