Despite current conditions of oversupply, the LNG market is set to embark on a growth spurt over the next five years. The relatively long lead times for liquefaction terminal construction provide good visibility of supply volume growth towards 2020. And volume growth will be substantial even if it is only limited to projects already under construction.

More than 100 mtpa (138 bcma) of new LNG capacity is currently being built, half of this in Australia. More than 40 mtpa (55 bcma) of that volume is due to be commissioned by the end of 2016, across Australia, Malaysia, Indonesia and the first US export trains at Sabine Pass.

After several years of limited growth in new liquefaction capacity there is a mountain of new supply entering the LNG market. What is less clear is whether anticipated Asian demand growth will arrive in a timely fashion to absorb new supply.

Where is the new LNG coming from?

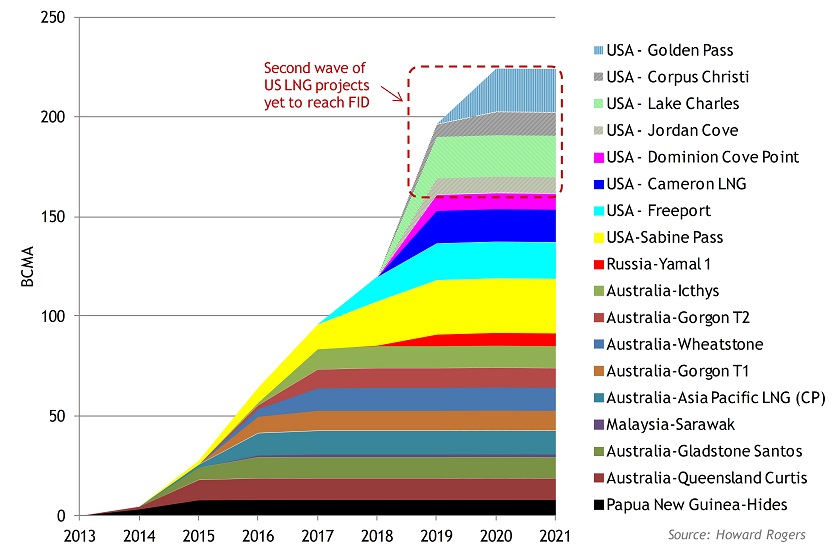

Chart 1 shows more than 150 bcma of liquefaction capacity that has reached Financial Investment Decision (FID) sign off and is set to be built by the end of the decade. The majority of this export volume will come from Australia and the US, both of whom are vying to substantially increase their presence as gas exporters. In addition, there is a ‘second wave’ of US export projects which are at an advanced planning stage but still awaiting FID sign off. If these volumes are included potential supply growth by the end of this decade swells to over 200 bcma.

Australia vying for the heavy weight title

By the end of this decade Australia is set to overtake Qatar as the world’s largest LNG exporter. Projects under development can broadly be split into two groups:

- Queensland: Three separate projects are being developed on Curtis Island (off the coast of Gladstone) to export coal seam methane (connecting the eastern Australian gas network to the global gas market).

- Western Australia: The Chevron led Gorgon and Wheatstone LNG projects off the Pilbara Coast and the Japanese led Ichthys project in the Browse Basin will add to Australia’s existing WA based liquefaction capacity.

In total these projects account for almost 70 bcma of new gas exports under construction, the majority of which is scheduled to be delivered by 2018.

In theory Australia has the potential to grow its LNG exports further via the expansion of existing terminals as well as the development of new ones. But Australia has a cost problem given a strong currency, high labour costs and difficulty in accessing gas. It has become renowned as the most expensive place in the world to develop new LNG projects (e.g. 20-30% more expensive than the US & East Africa).

The recent decline in the Australian dollar may be starting to assist with this cost problem. But cost recovery on any new Australian export capacity will likely to require contract prices of at least 11 $/mmbtu for brownfield expansions, rising to in excess of $14/mmbtu for further greenfield projects.

The new waves of US export capacity

A first wave of about 50 mtpa (70 bcma) of US export capacity is under development for delivery by 2019. This consists of the first four trains at Sabine Pass, as well as the Freeport, Cameron and Dominion Cove projects, all of which have FERC approval and have secured long term capacity contracts.

However the current global oversupply environment may be exacerbated by the delivery of a ‘second wave’ of US liquefaction projects. This additional 50 mtpa of ‘second wave’ US projects are either contracted or covered under ‘heads of agreement’, but are yet to reach FID and commence construction. Until market conditions recover, this second wave of US projects are likely to face delays or even cancellation. However at current Henry Hub prices, this capacity does look to be the most competitive source of new LNG capacity beyond the projects currently under construction.

In the short to medium term, the project economics of other US export projects that are yet to find buyers looks to be very challenging indeed. Intrinsic margins from US exports to Asia and Europe have collapsed over the last 12 months, reducing the willingness of buyers to pay for capacity. Contract buyers are likely to be hard to find until crude prices recover and the current wave of new LNG supply has been absorbed.

Will the anticipated demand turn up?

New LNG supply volumes can be projected with relative confidence given liquefaction projects are already contracted and under construction. But there is much greater uncertainty over the timing and volume of anticipated growth in LNG demand. This opens up the possibility of a significant timing mismatch between new supply and demand which tips the global gas market out of balance.

New liquefaction capacity is being developed against a backdrop of a structural increase in global gas demand, particularly in Asia. However a significant volume of new LNG is being contracted by portfolio players, rather than on a destination specific end-user basis. In addition, a number of higher growth importing nations (e.g. China and India) have relatively low long term contract levels.

The greatest demand side uncertainty sits with China. Over the last 12 months, China has been dampening industry expectations around its much anticipated increase in LNG demand. This is consistent with the signing of 68 bcma of framework agreements for pipeline imports from Russia. But the ongoing development of Chinese regas capacity is setting up the option for significant growth in LNG imports at the right price.

More broadly, Asian LNG demand is also vulnerable to a weakening global economic growth outlook and the prospect of Japanese nuclear restarts. Falling LNG prices may induce some demand response, particularly from more opportunistic buyers such as China. But when committed new supply is overlaid on a weakening demand outlook, the global gas market looks to be heading into a period of pronounced oversupply towards 2020.