Growing momentum to decarbonise the power sector is reshaping the European capacity mix. On the one hand, successful renewable support schemes are rapidly boosting intermittent renewables capacity. On the other, regulatory driven coal and nuclear closures are structurally reducing flexible capacity.

“Capacity prices tend to be self correcting… if prices fall too low, existing capacity closes and prices rise to support new build”

But does one effect offset the other? We recently set out the numbers behind why the answer to this question is no. Europe faces a growing flexible capacity deficit across the first half of this decade. And the success of renewables roll out is eroding the price signals required to support flexible capacity (the ‘missing money’ problem).

European governments have gradually cottoned on to this problem. They have introduced capacity payment mechanisms to underpin reliability via incentivising both new and existing flexible capacity.

In today’s article we summarise how investors approach capacity markets and take a tour of Europe to see how the schemes stack up.

4 key investor requirements

Capacity payments interact with other revenue streams to drive an asset investment case. Payments can be a key source of stable revenue to support fixed cost recovery and financing. But there are some key criteria that impact an investor’s assessment of the robustness of this revenue stream.

Regulatory stability & transparency

In general, European markets are relatively stable from a regulatory perspective. All the schemes we consider below have now been through the EC state-aid approval process. But capacity mechanisms are subject to refinement and transparency around policy changes is more varied.

Open and transparent policy is key to ensuring that asset owners’ opinions and concerns are addressed and pivotal in ensuring that capacity schemes achieve their intended goals. UK style policy transparency is not always evident in Italy & Spain.

Structural requirement for new capacity

Capacity payments are designed to do two things: sustain existing flex and/or incentivise additional flex. Building new capacity is more expensive than supporting existing capacity. So markets with a structural requirement for new capacity will tend to have higher clearing prices (e.g. Poland).

Power markets across Europe are broadly unified in their trajectory towards decarbonisation, but each market has its own starting point. This results in significant differences in new build requirements. The volume and timing of incremental capacity requirements drives capacity price formation.

Market Design

Every capacity scheme is unique, combining different obligations and incentives. Understanding how these obligations and incentives fit together is key to determining whether a capacity mechanism will support a specific asset.

Inflation indexed 10-15 year payments (e.g. in UK, Italy & Ireland), substantially increase the bankability of capacity revenue streams for new build. For existing capacity, one-year contracts can be more attractive as they provide more flexibility and do not commit asset owners to run longer than is economical.

All capacity schemes place some obligation on availability, but some also impose a cap on achieved spot power prices e.g. Italy & Ireland. Under such contracts, when spot prices exceed a pre-set strike price, capacity holders are required to pay back the difference. For peaking flex, such a cap can undermine an investment case by reducing energy revenue upside.

Pricing dynamic

The stability of capacity prices directly impacts the discount rate investors apply to the capacity revenue stream. A visible track record helps here, as does a structural requirement to deliver new capacity.

Excess price volatility undermines the purpose of a capacity market in supporting fixed cost recovery. For example prices slumping to zero has not helped the credibility of the French capacity market.

But one important factor that helps investors is that capacity prices tend to be self correcting. If prices fall too low, existing capacity closes and prices rise to support new build.

Tour of European capacity mechanisms

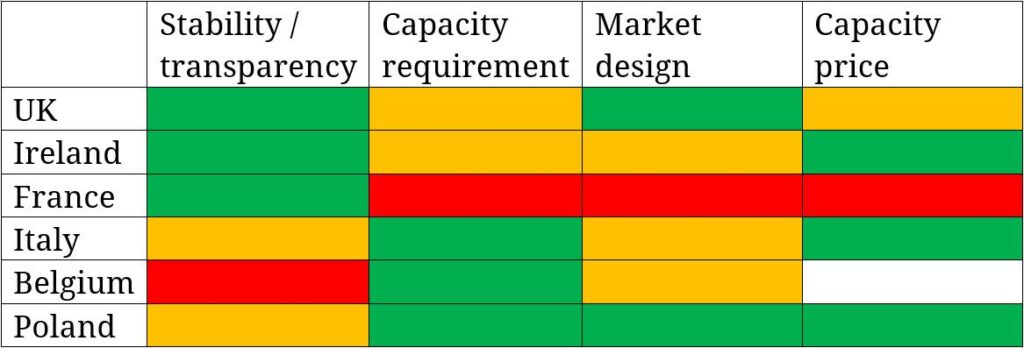

So how do European schemes stack up against these key investor criteria?

UK

The UK is the most mature of Europe’s recent wave of capacity markets having started in 2014. Aside from the temporary impact of a dubious ECJ court ruling, the market has run relatively smoothly.

The UK capacity market supports new build plant via capacity contracts up to 15 years in length, with 1-year contracts for existing capacity. Prices around 20 £/kW (24 €/kW) in the first three T-4 auctions supported significant volumes of new build. But the last two auctions have cleared at much lower prices (6-8 £/kW) as an overhang of older existing plants is removed.

Looking forward, the outlook for UK capacity prices is more constructive. 4GW of nuclear and 8GW of coal capacity are closing by 2024, as well as older CCGTs. This underpins a steady requirement for new capacity.

France

The French capacity mechanism followed the UK. Prices have generally been in the 15-20 €/kW region but a recent €0/kW auction for 2019 undermined confidence in the mechanism. The French regulator has indicated it is considering a review.

New build plants can tender to fix contracts for up to 7 years, shorter than in other markets, weakening the case for new build capacity. This partly reflects the fact that France has limited near term new build requirements.

Ireland

The Irish mechanism was based on the UK model but with 2 key changes. Firstly, spot revenues are capped at a pre-defined strike price. Secondly, new build contracts are limited to 10-years.

Recent auction prices have been supportive of new build, reaching 46 €/kW. Ireland is closing coal, peat and older gas-fired capacity. However it is a relatively small market and has some strong locational considerations driving capacity requirements.

Poland:

The Polish scheme is based on the UK and has a similar market design. Prices however have been significantly higher. The first 4 auctions resulted in a 45-60 €/kW price range, reflecting the need for significant new build. 90% of the existing flex fleet is lignite/coal and will be ineligible for capacity support under EU law from 2025.

Italy:

Similar to the Irish scheme in design, the Italian mechanism combines a spot price cap with conventional capacity payments. However, unlike the Irish mechanism, new build plant is eligible for up to 15 years of support. All coal plant is excluded from the scheme.

The large capacity overhang in Italy is gradually being eroded, particularly in localised regions where coal plant retirement combines with ageing CCGT. The first auction saw prices of 33 €/kW for existing capacity and 75 €/kW for new build (both hitting their respective price caps). This has sparked renewed investor interest in Italy.

Belgium:

The proposed Belgian scheme is similar to the Italian scheme and is designed to replace the existing strategic reserve to provide new build price signals. It has just taken a long time to develop with several reincarnations. But Belgium’s outlook is one of the most supportive in Europe for new build. The whole nuclear fleet is scheduled to retire between 2022-2025, removing what is currently 50% of Belgium generation output.

The Rest

We have recently highlighted the looming capacity crunch in Germany, however its capacity support strategy has so far been ad-hoc. A strategic reserve is in operation focused on controlled closure of older capacity. There is also some specific support for CHP. But as yet Germany has no market wide scheme. This may change as the reality of the capacity crunch starts to bite.

Spanish CCGTs have historically received two forms of capacity payment: (i) an availability payment (~5 €/kW) which was suspended in 2018 as a result of EU state aid review and (ii) an investment subsidy (~10 €/kW), with 70% of CCGTs set to lose this from 2020. The way forward for capacity payments has not yet been resolved by the new Spanish government.

Optimistic outlook for capacity revenue

Capacity payments have become the accepted European solution for underpinning system reliability as power markets decarbonise. Yet investor confidence in capacity revenues has been somewhat undermined by a combination of teething issues and an overhang of existing capacity.

Each scheme is unique and has its own strengths and weaknesses. But a growing structural requirement for new capacity across the next 5 years is set to support capacity prices across Europe.

Coal and nuclear closures cannot be offset by intermittent renewable generation alone. This underpins the need for investment in new flexible capacity across storage, gas, demand response, interconnectors, flexible renewables and hydrogen. Capacity payments will play a key role in delivering that investment.