When the UK capacity market was introduced in 2014, large grid connected CCGTs were anticipated to be the primary provider of new capacity. Step forward five years and it is distribution connected gas reciprocating engines that have taken the largest share of the pie.

The success of gas engines has been driven by a combination of relatively low capital costs, very fast ramp rates, low start costs and attractive levels of embedded benefits to supplement wholesale & balancing mechanism (BM) margins. The challenge now confronting engine owners is that policy changes will remove most of the embedded benefits margin over the next 18 months.

This means that engine returns going forward will be firmly focused on wholesale market and BM margin. Key structural drivers should support this merchant margin into the 2020s. But the last two years have been more difficult for engine margins. In today’s article we show a simple ‘backtest’ analysis of merchant engine margins, explore margin drivers and consider the broader implications for the UK power market.

The evolution of engine margins

Enthusiasm for gas engine economics was helped by very strong margins in Winter 2016-17 as a result of market tightness caused by large French nuclear outages (e.g. causing UK interconnectors to export rather than import power). Enthusiasm was also fuelled by some very ‘optimistic’ consultant forecasts at the time that extrapolated similar conditions into eternity.

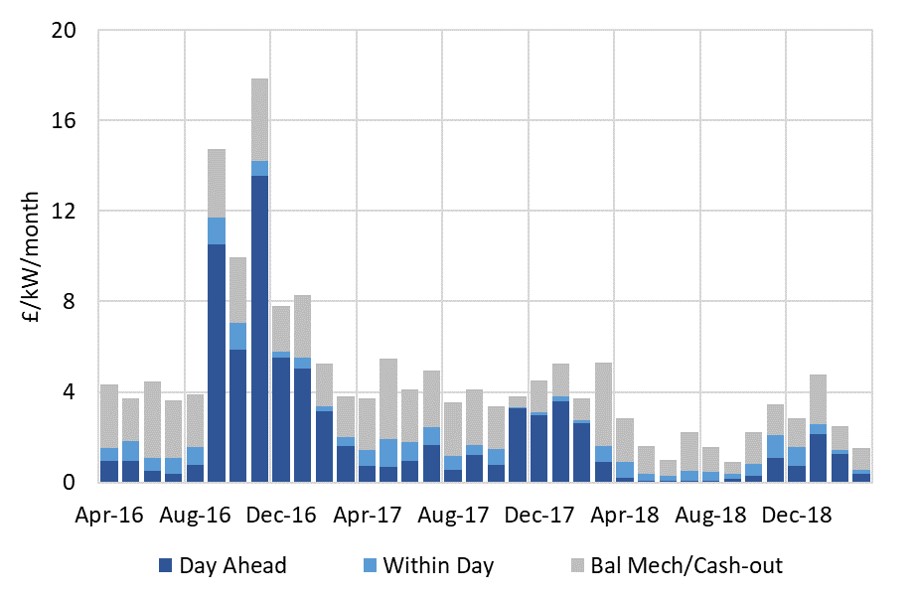

Chart 1 shows the reality of a return to much tougher margin conditions over the last two years, particularly across the last 12 months. The chart shows value capture across the Day-Ahead market, Within-Day market and Cash-out prices for a 35% efficient embedded reciprocating engine, assuming a merchant value capture strategy.

Note the chart does not show ancillary (e.g. STOR/FR) or embedded benefits (e.g. triads, GDUoS) margin streams. Cash-out price value capture numbers are based on a NIV chasing strategy.

Two warm winters have followed 2016-17 with UK electricity demand surprising to the downside. This has been exacerbated by an overhang of thermal capacity versus Capacity Market expectations (e.g. delayed retirements of Eggborough coal & Peterhead CCGT plants).

In addition, peak prices have been dampened by increasing volumes of engines running to try and capture triad period revenues. This is however a temporary dynamic that will fall sharply over the next two winters as policy changes see the triad benefit reduced to almost zero.

Cash-out price (or Net Imbalance Volume) chasing has become a key focus of engine portfolios. This relies on accurately forecasting cash-out prices and running associated imbalance volumes to generate value. Margin capture from this strategy is being challenged by:

- Increasing volumes of engines coming online and pursuing a similar strategy

- Players using similar forecasting techniques to predict cash-out prices.

The volume of flexible capacity now chasing cashout prices significantly outweighs the average system imbalance volumes. Asset owners are recognising that engine value capture will need to transition to a more conventional Balancing Mechanism bid/offer strategy over the next 2-3 years.

While conditions have been difficult, this does not spell the demise of the role of engines in providing peaking capacity. Just as it made no sense to extrapolate Winter 2016-17 conditions forward, it is unrealistically pessimistic to extrapolate conditions over the last 12 months. It is normal for value capture from ‘out of the money’ peaking assets to fluctuate significantly across years: 2016 was a big year, 2018 was a tough one.

Two important implications of current environment

The evolution of engine margins is likely to have some broader implications for the UK power market.

Firstly, capacity market bids for engine projects will almost certainly rise. Investment cases that supported sub 10 £/kW capacity bids are being strongly challenged by current market conditions. GWs of ‘cheap’ new build and DSR related engines have helped pull down UK capacity prices since introduction of the capacity market. Engines will continue to play a key role in providing new flexible capacity in the 2020s. But engine investment going forward is likely to require significantly higher capacity prices than the last T-4 auction.

Secondly, tough conditions could well trigger significant aggregation across UK peaking portfolios. A strong trading and commercial analytics capability is quickly becoming a key differentiator across peaking asset portfolios, as the importance of wholesale/BM margin increases. This capability is expensive to outsource and takes time & money to build in-house. Step forward 3-5 years and it would not surprise us to see several large players with strong commercial & trading teams dominating the provision of UK peaking flexibility.