Billions of pounds are being invested in flexible peaking capacity in the UK, as the coal fleet closes and older gas plants retire. The two dominant technologies being deployed are gas reciprocating engines and shorter duration lithium-ion batteries.

Only a small volume of this new peaking capacity currently operates in the UK’s Balancing Mechanism (BM). But the BM is set to become the primary driver of value for both engines & batteries across the 2020s.

In today’s article we look at what types of capacity are currently competing in the BM to provide flexibility services. We also look at how this is likely to evolve given capacity mix changes across the next 5 years.

Why will the BM be so important?

Margin capture for UK engines and batteries is currently focused on:

- ‘NIV chasing’: forecasting cashout prices & trying to run imbalances to capture margin accordingly (see here for article on battery challenges in chasing cashout prices)

- Triads: running in periods of peak demand to help reduce supplier charges

- Ancillaries: providing services such as STOR, frequency response (e.g. FFR) and fast reserve

Step forward five years and it is likely that BM value capture will dominate all of these sources of margin capture for most peaking assets. But why such a rapid margin transition?

Market participants increasingly recognise that NIV chasing is a dying game. Average system imbalance volumes in the UK are typically only several hundred MWs. Yet there will soon be GWs of flexible capacity chasing relatively small imbalances. That will increase forecasting errors & risk and reduce returns. The practice of intentionally running large imbalance volumes into gate closure is also likely to attract the attention of regulators, who may implement rule changes to disincentivise this.

Margin from triads and ancillaries is also declining. Triad revenue will largely disappear by 2021 as a result of policy changes already announced. And increasing competition to provide frequency response, STOR and fast reserve services has been driving down returns for these balancing services.

The combination of these factors means the future for flexible peaking capacity is likely to be focused on capturing value in the BM and prompt forward markets (e.g. Day-Ahead and Within-Day markets).

Balancing Mechanism 101

The BM is the mechanism that the system operator (National Grid) uses to balance the UK electricity market in real time. Market participants that are registered as ‘BM Units’ can submit bids and offers in the BM, reflecting prices at which they would be prepared to flex down or flex up respectively.

National Grid then uses a combination of these bids & offers as well as other balancing services contracts to ensure the system balances in real time. This task is becoming more challenging over time as wind & solar intermittency increases. But that is also creating increasing opportunities for flexible assets to capture margin in the BM.

An important distinction between the BM and the wholesale market is that all participants are ‘paid as bid’ not paid the price of the marginal provider of energy. This in combination with volatile prices, means that there can be some very lucrative opportunities in the BM, during periods of system constraint.

The flip side of very volatile prices is a relatively high level of volume risk. Capacity owners do not know when they place bids & offers whether they will be accepted or not. Therefore value capture in the BM often has a significant opportunity cost linked to foregone margin from the wholesale market.

What capacity provides BM flex & how will this change?

Flexibility requirements in the BM can be summarised as:

- Flex up: the ability to provide more energy to the system (or reduce demand)

- Flex down: the ability to reduce output onto the system (or increase demand).

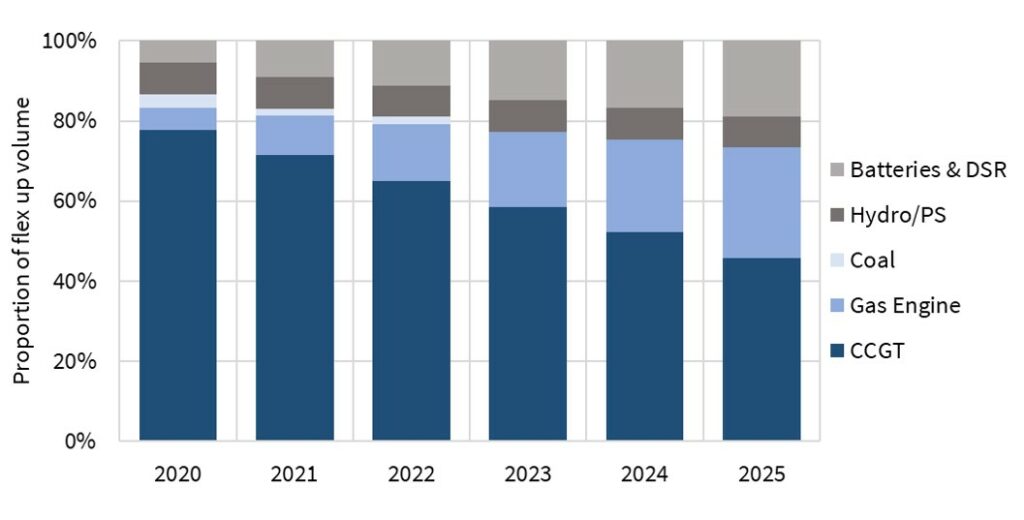

Chart 1 provides an illustrative scenario of the evolution of the percentage of different technology sources providing Flex up volumes across 2020-25.